I am struggling to answer this question: “how can I explain Brexit to my Ukrainian friends?”.

While I was living in Kyiv – more or less 2 years ago – I stood on Maidan square, the epicentre of the Ukrainian winter revolution.

Also known as Euromaidan, those popular protests started in Kiev, in the night of 21 November 2013, when the then Ukrainian President – Mr Viktor Yanukovych – decided to suspend preparations for the signing of Ukraine’s Association Agreement with the European Union. The movement was violently repressed, and the clashes that ensued, lasting for a few months, led to the fall of Mr Yanukovych and the election of a new government and president. Events that followed are Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the War in Donbass.

During those cold months of Euromaidan protests, I have witnessed people fighting, getting injured, and in numerous instances losing their life. They were not really fighting for the EU as a supranational institution per se. Rather, they were fighting for the values embodied by the European Union, which makes it equally important: dignity, democracy, free movement of labour, goods and services, rule of law, balance of powers within the State, less corruption. The protesters of Euromaidan managed to overthrow a president that was trying to delay the country’s integration process towards the EU. They knew what it was to live without Europe, and they wanted more of it.

Now, in a calm London Sunday morning, finding myself in a city that seems to have waken up after a very bad dream, I think how challenging it would be to explain to those Ukrainians, men and women, the reasons why 17 million people in the United Kingdom have expressed their willingness to leave the European Union in last Thursday’s referendum.

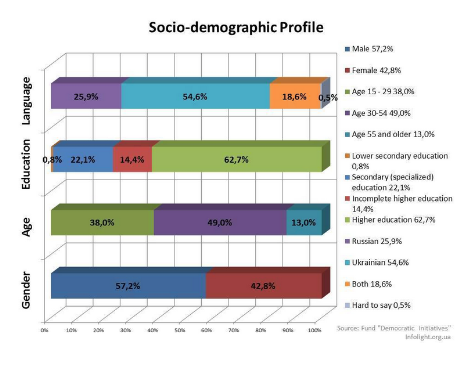

Indeed, the two sentiments expressed by the Ukrainian events and by the British referendum appear very different at first glance. On the one hand, desire of more integration; on the other, desire to separate. However, it actually occurred to me that the average socio-demographic profile of the Euromaidan supporter is extremely similar to the profile of those who have voted Remain in the recent referendum. Therefore, it seems the two events are not so dissimilar as they first appear. While this leaves a ray of hope, it also opens room to many other questions.

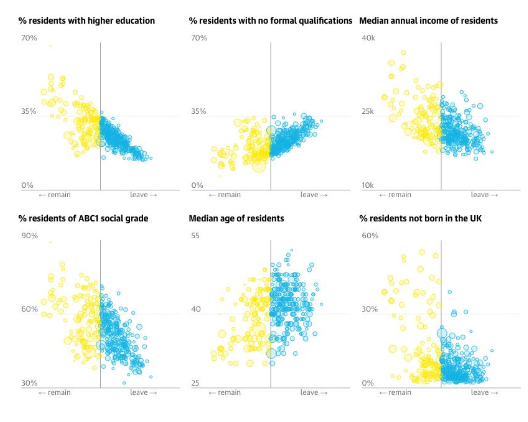

Looking at the data below, it seems that (on average) those who aspire for more integration – both in the case of Euromaidan and the UK referendum – are the young (“generational” divide), the most educated (“educational” divide) and those living in certain geographical areas (“geographical” divide).

Figure 1 – UK referendum voter analysis

Figure 2 – Socio-demographic profile of Euromaidan protesters

Therefore, it is easier to explain the UK referendum results to my Ukrainian friends not as a lack of the willingness to adhere to all the values embodied by the European Union. Rather, we can argue that it is a function of the ever-growing “divides” in UK society, whereas the majority of the population (in terms of average profiling) is less educated, feels geographically more divided and it is growing older, and perhaps becoming more reactionary as a consequence.

It is entirely possible that the British people will get to understand the importance of being in the UK when they will be privy of it, just as the Ukrainians sought more European integration when they did not have it. But in any case, to get the United Kingdom closer to the European Union again, the politicians will have to manage to overcome those internal divides that currently prevent integration WITHIN the UK society. When they will be able to educate the population, to have youth participating more actively in the political life of the country, and to feel the countryside citizens less isolated and make them participate to the economic boom of the cities, only then the UK might desire to be back on track in the road of European integration.

I am sure my Ukrainian friends will understand.