Social Impact Bonds are one of the latest financial innovations in the field of public welfare. A recent report published by Social Finance (the creator of this innovative financing mechanisms), take stocks of the progress to date, 6 years after the first Social Impact Bond was launched. It discusses the state of the art of the Social Impact Bond market, the key benefits to the public authorities and the investors, and the key risks and weaknesses of this funding model.

What are Social Impact Bonds?

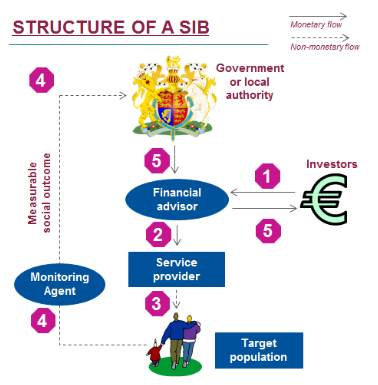

They are essentially an innovative form of Payment By Result (PBR) scheme, a contract according to which the Government (or a public entity) commits to pay for improved and measurable social outcomes. On the back of this contract, capital is raised upfront from private investors (1, figure left). This capital is then used by the service provider to fund a range of social interventions on a target population (2,3). Investors are repaid by the public authority if and only if the measurable social outcome is reached (4,5). They stand to lose money (fully or partially) if the social outcome is not reached. Therefore, investors bear the risk that the interventions do not deliver the contractually-agreed (measurable) social outcome. The greater the improvement, the greater the financial return to investors.

Peterborough Prison – the first SIB

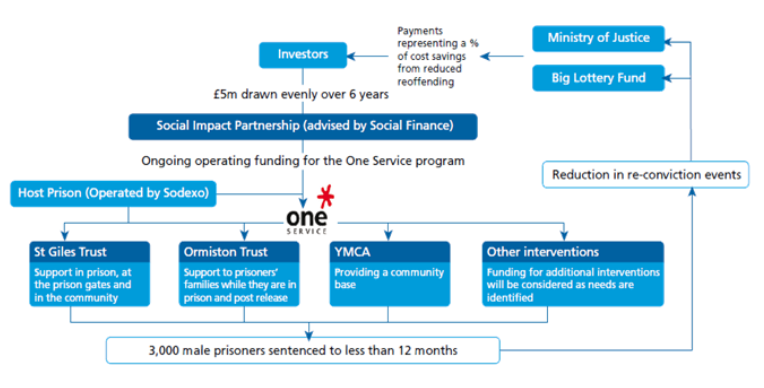

The first Social Impact Bond to be launched was at the prison of Peterbourough, in 2010. The UK Ministry of Justice (in cooperation with the Big Lottery Fund) entered into the first SIB mechanism with Social Finance, a private financial intermediary, the arranger of the scheme. Below is a full overview of the contractual arrangements underpinning this first SIB.

Through this Social Impact Bond, Social Finance raised ca. GBP 5.0MM from 17 trust charities, ethically oriented investors and corporation trusts (including the well known Social Venture Fund, King Baudouin Foundation, Barrow Cadbury Trust, Big Society Capital, Esmee Bairbairn, the Tudor trust, Bridges Ventures, and Charities Aid Foundation). This money is being used to pay for interventions for 3,000 male offenders serving short-term prison sentences (<12 months) at Peterborough prison (the “target population”).

Interventions to the target population include: i) psychological counselling; ii) 1-to-1 meetings; iii) help to secure accommodation, iv) access social benefits and get a job following the release from prison; v) psychological and practical support to families during the time prisoners serve their sentence in jail.

The pay-out to investors is linked to the measurable social outcome to be achieved by the interventions: if the independent monitoring agent calculates that REOFFENDING (defined as number of reconviction events over 12 months after release) has reduced by at least 10% for each cohort, or 7.5% overall, compared with a “control group” not subject to the interventions, the Ministry of Justice has undertaken to repay the investors, plus a return on investment. The return is directly proportional to the % drop in re-conviction rates vis-a-vis the control group, and ranges between 2.5% and a maximum of 13% p.a.

The SIB has an 8-year term, with capital drawdowns made annually in years 1 through 6. Payments to investors, if they become due, occur in approximately years 4, 6, and 8.

An interim evaluation monitoring report for Peterborough SIB was released in April 2014 and followed-on on 7 August 2014. For the first SIB cohort, the number of Short-term offenders discharged during Sep10-Jun12 was 1,006 and their re-conviction rate in the next 18 months was 8.4% lower than the control group. An early payment would have been triggered if re-conviction fell more than 10% vs. control group. Despite no early payment for first cohort, as of June 2016 the overall programme is on track for payment in 2016, if 7.5% reduction is achieved across the project.

In general, during the first evaluation report, it came evident that the market gap was there, and the idea was well received by the UK Ministry of Justice. The Government has therefore decided to scale up short-term offenders rehabilitation, rolling-out a nationwide funding scheme, the Transforming Rehabilitation Initiative. However, Transforming Rehabilitation was rolled out under a traditional government funding scheme, not using a SIB approach. To many extents, this indicates the success of the SIB in evidencing and addressing an initial social need, but still challenges in reaching the adequate scale of a full intervention set using the scheme.

6 year progress – the state of the art

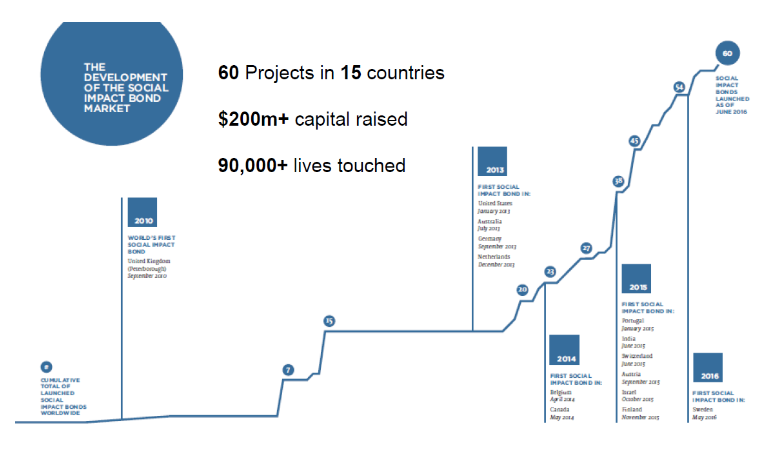

After 6 six years, several Social Impact Bonds schemes have been launched all across the globe. As of June 2016, Social Finance was able to track down 60 SIB Projects in 15 countries, for a total of more than USD200m capital raised and more than 90,000 lives affected by the SIB-funded interventions.

Target populations have included so far: a) Prison offenders b) Disadvantaged/Unemployed Youth, c) Homeless, d) Low-income families with children, e) Migrants / Refugees f) Single mothers g) Indigenous populations, h) Isolated older people.

Enabling legislations were passed in the UK, US, Canada, Australia, France, New Zealand, Portugal, Canada, Peru. Also, during the first years, a number of governmental entities were created to facilitate adoption and implementation of Social Impact Bonds: the Centre for Social Impact Bonds (UK), Office of Impact Investing (Australia), Social Impact Partnership to Pay for Results (US), Portugal Inovacao Social and many others. Supranational institutions have also shown an early interest and started to embrace the SIB concept: the IADB has allocated USD 5MM to invest in SIBs, the first multilateral financial institution to do that). The EIF – part of the EIB group of the European Communion – has closed in 2015 a Social Impact Accelerator Fund (SIA), a fund of fund of EUR243 MM that will also support Social Impact Bonds funds.

Systemic performance data reporting and consistent aggregation have so far been challenging, mainly due to the early life of the scheme: many SIBs have just started operations, and for several others only preliminary results are available. Nonetheless, as of June, out of the 22 SIBs that reported performance data 21 indicated positive social outcomes. 12 have made outcome payments and 4 have fully repaid investor capital.

Benefits to government & investors

Social Impact Bonds are supposed to provide obvious benefits to the target population who is subject to the interventions. Less obvious are the benefits to government and to investors compared to a traditional social intervention funding scheme, which we will discuss down here.

From the government perspective the SIBs:

- Align public sector funding more directly with improved social outcomes, correcting poor incentives

- Increase the pool of (private) capital available to fund prevention and early interventions

- Provide greater certainty over revenue streams for effective service providers

- Encourage a more rigorous performance management including objective measurement of outcomes

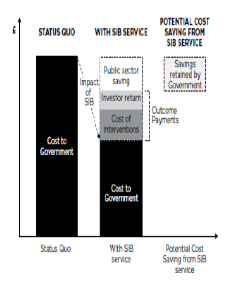

- Achieve a real risk-transfer: the Government will not pay if the outcome is not reached

- Enable saving in social capital compared to a lack of intervention on the target population or to an unsuccessful intervention.

From the investors’ perspective, SIBs can provide:

- A blended social return: contribute directly to solve or mitigate a social issue. They are supposed to allow good publicity in the community.

- Potentially attractive financial returns for the risk borne, at a times of low market interest rates

- A diversification benefit. New asset class with minimal correlation to any other available investment product (see “core-satellite” portfolio allocation).

- In certain cases, a tangible benefit related to investors’ primary activities, e.g. insurance companies can benefit from crime reduction

- A learning opportunity and room for innovation

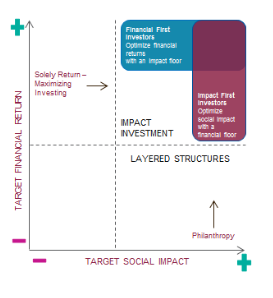

In general, Impact Investments will mostly appeal to those investors who are seeking to maximize both financial return and social impact, even with varying priority, according to the table on the left.

Key risks and challenges

The recent report published by Social Finance – and earlier research into the Social Impact Bond concept – has also highlighted a number of risks and weaknesses present in the model which I will summarise below.

Intervention model risk

- Poor screening and checking of the selected intervention, which may fail to produce the expected social outcomes or produce sub-optimal results just to conform with the performance metrics.

- The due diligence process should provide an understanding of the intervention model, project cash flows, and the capacity of the non-profit providers.

Intermediary risk

- Failure of the intermediaries to add value to the SIBs from deal origination through investor repayment.

- Failure of the intermediaries to commit to SIBs over the long term, either due to changing internal priorities or weak financials or governance, expose SIBs to greater risk.

Financial Risk

- Investors bear 100% of the financial risk in a SIB, as they provide upfront funding with uncertainty of capital repayments and returns (equity-like).

- Lack of secondary market liquidity and deep track record

- Risk-mitigation methods (e.g., tranching, first-loss, escrows) could be incorporated into the SIB structure [but avoid dilution of risk-transfer]

Execution risk

- Unique vulnerabilities inherent in the SIB operating model. Risk to face unclear lines of authority, lack of follow-through by one or more partners, or failure to capture timely and reliable data on progress.

- Lack of sufficient implementation capacity by the service providers. Not easy scale up (see Peterborough)

Political risk

- Possibility that the government challenges the achievement of the pre-defined outcomes or reneges the programme as a whole.

- Government credit risk, or failure to meet their obligations to investors

Reputational risk

- Significant risk that the failure of the intervention can procure reputational damage to the non-profits, the investors and ultimately the Government, especially considering the innovative character of the tool and media attention.

- Mitigation possible with adequate PR, network of contracts and attention to public reaction.

When entering a SIB mechanism, each of the presented risks has to be assessed carefully, monitored and possibly mitigated, and weighted against the benefit of a SIB funding structure vis-a-vis a traditional intervention.

Conclusion

At times of constrained state budget resource, there is an increasing demand for private capital to do more in the field of social welfare. From this perspective, the Social Impact Bonds can help align incentives for all parties, despite still requiring continuous monitoring, cooperation and risk mitigation to ensure the success of the intervention and ultimately return of capital to the investors. Strong legal foundations in the host country are also crucial to ensure that the appropriate net of contracts can be put in place to enforce the SIB schemes.

Despite being difficult to consistently track performance – also due to the early age of this scheme – the first evidence is comforting. In this direction, we advocate for ever-increasing transparency of performance data, regular publication in a structured format and possibly the creation of an index to track spot-on progress.

The public institutions have a crucial role to play to create an enabling environment, including through legislation. In this direction, we advocate a greater role for supranational institutions (for example large multilateral financiers, such as IFC, EIF, EBRD, ADB, etc